By Frederick Karinthy

Courage, My Boy

HUMOUR

WHEN I read about the great professor’s latest discovery, I was too excited for words.

He had discovered that courage and cowardice were determined not by personal disposition, but by a nerve in the back of the neck, and that if this nerve was severed in any person, that person became as courageous as the bravest person in whom this nerve had not been severed, comparison between people thus treated and ordinarily courageous people being impossible.

At first I dared not believe my eyes, but subsequently I argued that the reason I dared not believe my eyes was that I was still a coward, my nerve not having been severed; as soon as it was severed I should have the courage to think that I was not a coward.

I did not call on the professor, nor did he call on me. We met in neutral territory.

“Sir,” I said timidly, “I venture to inquire—”

“You can’t venture,” interrupted the great man severely, “until your

nerve is severed.”

“Well, then I humbly beg you to sever it for me.”

“That’s different,” he said. “Sit down. I’m going to slit open the back of your neck and cut through the nerve. Then you’ll be as brave as a lion.”

“But,” said I, “I’m afraid. I’m a coward.”

“That’s why I want to cut through that nerve.”

“This is very puzzling,” said I, scratching my head. “In order to let you slit open my neck I must be brave; and in order to be brave I must let you slit open my neck. Umm.”

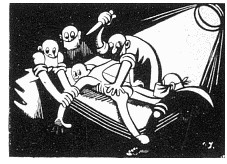

The next instant I was seized by four half naked, snarling assistants who, with lancets drawn, dumped me on a table, and at a bark from the professor they made an incision on the back of my neck.

Whereupon I leapt to my feet and proved the complete success of the operation by giving one of the assistants a mighty swipe across the face.

“Congratulations, my boy,” said the professor, holding out his hand

325

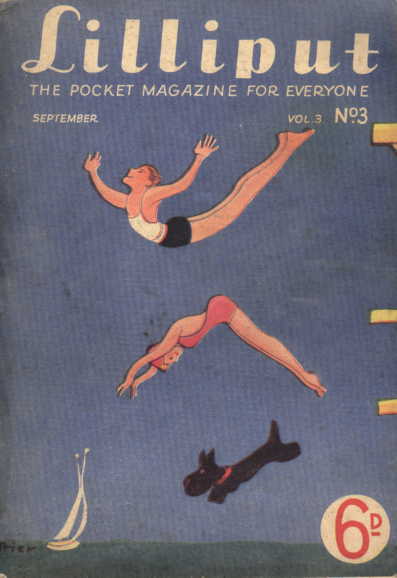

LILLIPUT

and smiling.

“As you see, the operation’s been a marvellous success. You may pay me the fee of fifteen pounds at once.”

“Is that so?” I said bravely. “I’m not going to pay you anything at all.”

I was jubilant. But for the operation I should have said the same thing timidly.

I strutted haughtily out into the street.

I whistled aggressively and looked round for someone to pick a quarrel with.

A pretty woman was walking in front of me with her husband. I just pushed the fellow aside, and chucking the woman under the chin, I said:

“Hullo, sweetheart!”

Whereupon I received an awful punch on the nose, but I was not in the least afraid, and bursting into loud laughter I challenged the husband bravely:

“I’d like to see you do that again.”

The fellow punched me on the nose once more, whereupon I courageously attacked him, courageously intending to thrash him, but unfortunately he was the stronger, and while defending himself he cravenly and tremblingly punched me on the nose for the third time.

So terrified was he by my heroic conduct that he shook all over and his teeth chattered as though with ague, and he put up a desperate defence, but unfortunately he was stronger than I and he knocked out three of my teeth.

I thereupon courageously flung myself upon him once more, while he, deathly pale and sobbing with fear, defended himself again, bashing my head in and kicking me in the stomach, after which he cravenly took to his heels, while I remained heroically lying on the pavement in the street.

I went from the hospital straight to the professor and demanded to have my nerve stitched together again, otherwise I should thrash him within an inch of his life.

I had the courage to declare that I wanted to be a coward, a thing I should never have dared to say before I had my nerve severed.

The professor was frightened of me and stitched up the nerve. As I thanked him I kissed his hand and humbly begged him to allow me time to pay for his services, and since then I have been feeling all right again.

My only regret is that while my nerve was still severed I forgot to inform my publishers what I really thought of them.